The below biographical sketch of Hakan Julius Anderson is simply my attempt to source, collate,

order, and summarize all the information I could find on him. Some notes:

➢ I started this sketch talking about Hakan Julius’ parents in order for the reader to

understand the setting in which he was born as there is no first person account of his

youth. Håkan’s story takes up a little more than the first two pages. The father Håkan is

always written with the diacritic above the “a.” Hakan Julius is referred to simply as

Hakan. This hopefully helps the reader keep them straight.

➢ Some commonly held information was corrected when trying to validate it with other

sources.

Examples:

1. Most stories say Sarah Barney Anderson died of a broken hip. Her death certificate

says it was a broken femur.

2. I heard my own father talk many times about how Hakan interacted with Geronimo.

However, Geronimo was a POW of the US government before Hakan ever moved to

Arizona. Hakan and his daughters were chased by Indians, but how then could they

have been Geronimo’s braves? Thus I removed any reference to Geronimo.

3. Hakan couldn’t have used the life insurance money from Walter’s death to buy the

Pima Drug Store, as he bought the drug store a year before Walter’s death.

➢ Some information is told differently by different people. Contradictory information is

removed.

Examples:

1. Some say Håkan’s family was so poor they ate bran and greasewood greens every

day but Sunday. Another source said “for several weeks.” I simply put that they

were so poor they ate bran and greasewood.

2. One grandson said he knew Hakan went to church; most sources at least imply he

didn’t go often. They could both be true at different times of his life. So I simply

wrote about what he did do in the church and his support of the church.

➢ I did my level best to never assign emotions or feelings to people, nor make common

assumptions—no matter how many times something was repeated in stories.

Examples:

1. It would be very easy to assume Augusta died of the measles. But it is never

explicitly said that’s what she died of.

2

2. I would assume Hakan was extremely sad when Walter died. But I just quoted what

Hakan said at that time instead of saying “Hakan was sad.”

➢ This biographical sketch was written for all of his descendants—not just one child’s line.

It is written to be short in order to easily keep one’s interest—especially our youth. It is

in NO way intended to be a complete biography of him.

➢ Attached timelines I originally made to keep things straight in my mind. Hopefully it

helps you as well. I am not a graphic designer in any way.

➢ More areas to research on his line:

1. Was it Hans Peter Jensen, the prior Baptist preacher, who baptized Håkan? Where

else is Håkan listed in church records?

2. Many stories are told of Håkan traveling or working with horses. What source

material can be found for those? I had his marriage record translated from Danish.

It states that Håkan worked for the government as a warehouse worker/dock worker.

That is the first sourced information about the stories I have found.

3. Swedish genealogical research. Danish genealogical research.

4. More records that say “I remember Hakan (or Marie) telling me about. . “ specific

occurences.

5. Going through every year of the Graham Guardian for more references to “HJ

Anderson.”

For now, my sources are simply links without any proper MLA sourcing etc. My notes by the

sources may give you an idea of where a fact in my sketch can be found. It is simply my “rough

draft.” Some source notes are interesting in their own right. Many contain additional

information not included in the sketch.

Though written as “Once upon a time. . .” everything in this story is true. I wrote this way only

stylistically.

Feel free to reach out to me with comments, questions, or more sourcing that may change the

sketch as I have written. I am only interested in having the sketch be correct.

Jeana Lyons

Jeana>Benton>Laura>Hakan>Håkan

~~Written with the most tender, heartfelt love for the Scandinavian saints who suffered so much

to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—as well as to their posterity. You will

always be in my heart.

3

Once Upon a Time. . .

. . .there was a Swede named Håkan Anderson. He was born in a place called Hörröd in 1822.

He served in the Swedish military, was a farm worker, and worked as a mill worker on an estate

in Sweden. He moved to Denmark in 1851.

There he decided to work at the docks for the town of Frederiksberg. Soon he met a Danish

woman named Mariane Marie Nielsdatter, whom he called Marie. They were married on

September 14, 1853.

A few years before they were married, Apostle Erastus Snow from the Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-day Saints had come to Denmark. It was 1850 and he was there to open missionary work

for Scandinavians. There was much persecution towards those of the faith at that time. The

common saying in the country became, “To join with the Mormons is to have one’s windows

broken.” Scandinavians who joined the Church were shunned by neighbors and had to be

baptized secretly at night; some were killed, and homes of converts were attacked. Erastus

Snow said of these saints, “To embrace the gospel is almost equal to the sacrifice of one’s life;

and to travel and preach it, a man carries his life in his hands.”

Missionaries were beaten, hid to evade capture, put in jail on a diet of water and bread just for

preaching, and even had their homes surrounded by chanting mobs. Yet in most areas of

Denmark the missionaries were baptizing people weekly, if not almost daily.

Håkan Anderson met the missionaries and was later baptized on April 14, 1854. He was

rebaptized when Marie got baptized in May of 1858. Not only was it with great risk that they

joined the church, but they were also shunned by family:

“[Marie] said she used to get so lonely for her family she could hardly stand it, because

they had always lived so affabl[y] together. One time, when she knew the family was

together at a traditional birthday celebration, she dressed her two children in their best

clothes, took them by the hand and went past the family home hoping the family would

invite her in, but instead, in their bitterness, they came out and spit at her.”

But with the persecutions also came blessings:

“It is a record of triumphant spiritual manifestations—the sick made whole, enemies

routed, prophetic dreams and visions enjoyed, tongues spoken and interpreted, the

signs which follow believers multiplied—a Pentecostal outpouring of gifts so widely

experienced and reported that it seemed a special dispensation for Scandinavia.”

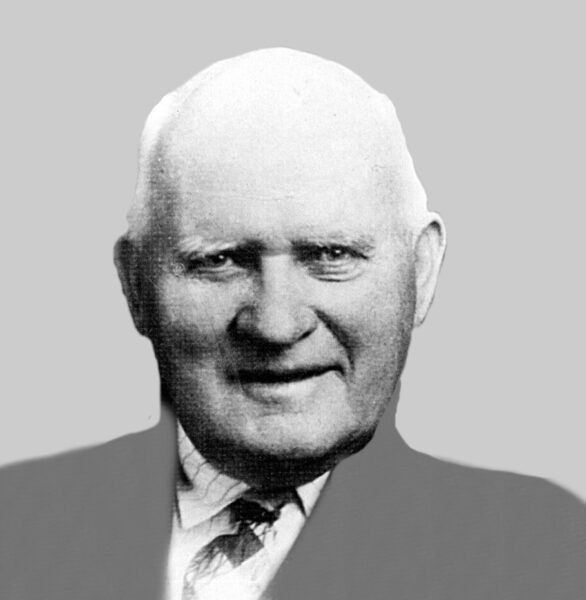

Marie gave birth to their third child, Hakan Julius Anderson, on September 4, 1858. And it is of

him we tell the story.

4

Getting to Utah from Scandinavia. . .

. . .was not easy. Brother Ola Liljenquist, a tailor, was the only member of the church in the mid

1850s Denmark who was a burgher. We would use words like “citizen” or “urban elite” to

describe a burgher today. A man had to prove his respectable employment, pay a fee, and have

others vouch for his character in a town he’d lived in for many years in order to obtain burgher

papers. Having possession of burgher papers enabled a person to do things most residents of

Denmark could not do, in particular when interacting with the government—like getting

passports.

Ola used his burgher papers to obtain Danish passports for thousands of Saints leaving for Utah.

He used them to vouch for Saints from other countries who had been fired from their jobs and

driven from their homes and were gathering to Copenhagen. He also used them to bring

soldiers–at least once with fixed bayonets–to protect the saints against mob violence. Ola was

also Håkan’s branch president.

Emigration was halted for a time due to the “Utah War”, but in 1858 President Brigham Young

said emigration from Scandinavia could continue. In 1859 the Saints were advised to do all

within their power to save means for their emigration. There was an “Emigrations-fond [fund]”

amongst the members of the church which led to a regular savings system for the trip to Zion.

Those saints with ample means helped those less fortunate. Sometimes savings were pooled to

enable a few to go–who later would send money back to help the rest. The Perpetual

Emigration Fund was also used. Håkan paid 113 rigsdaler into the Emigrations-fond for his

family’s emigration to Utah in 1862.

Ola had previously emigrated, but returned to Denmark as a missionary. At the end of his

mission, he was a leader of Håkan’s emigrating group. Under the direction of President Cott, he

and others gathered 1,556 Scandinavian saints to leave for Utah. Hakan Julius was 3 years old

when the Andersons left Copenhagen by boat for Kiel, Germany. From there they took the train

to Hamburg, then boarded the ship Electric to cross the ocean.

Four days after they set sail on April 25, tragedy struck. One passenger noted:

“On Monday the wind is still good but ‘sickness breaks out among us.’ Measles had

broken out. Tuesday – April 29 – The first death at sea – a little daughter of Brother H.

[Haukan] Andersen. [The passenger’s] Grandfather was there when she died. He ‘lifted

her into another bed.’ On Wednesday – the little child was put into the sea in her little

casket.”

Håkan’s fourth child, 2 year old Augusta, had tragically died.

The passengers lived on sailor’s provisions and water that went foul before they reached New

York in June. The Scandinavian saints got into a railcar in New York and travelled to Florence,

Nebraska. Once there, those that had money organized into 2 independent wagon companies

and left for Utah. The Andersons waited to be assisted by the teams sent from Utah, which

5

were late due to spring flooding. While waiting, Håkan’s family lived on the open prairie in the

heat. They attended church meetings in English that they couldn’t understand. Håkan used the

Perpetual Emigration Fund to buy two cows. The teamsters eventually arrived yelling, jumping,

swinging their hats, and capering around with an occasional pistol shot. This was an unusual

sight for these Europeans to look upon.

Håkan’s family left for Utah in the middle of June. They had quite some difficulty the first few

days. A fellow-traveler said: “We had some considerable trouble getting started from Florence

with those kind of horses, I mean oxen which there was provided for us.” The oxen, who were

not used to Scandinavian orders and management, would often follow their own inclination,

and thus there was more leading than driving them. The saints were astonished and considered

it quite the show when the teamsters used only commands to get the oxen to form a circle and

then quickly unyoked them.

Nothing out of the ordinary occurred on their trip but for a “terrible hurricane” in July that

caused damage. They finally arrived safely in the valley in October of 1862.

Håkan and his family. . .

. . .were called by Brigham Young to settle in Fillmore, UT. First, Håkan was in charge of a flour

mill. Then Håkan was asked to live in and help settle the nearby town of Deseret. While they

lived there, an “Anderson Dam” was built for water, and a fort was built to protect themselves

from Indians during the Black Hawk War. After three years the church leaders advised the

settlers to abandon the settlement. The family went back and settled just outside of Meadow,

UT on a homestead they called Dry Creek. They went to the Meadow Creek Branch of the

Church of Jesus Christ.

Seven more children were born to the family after they arrived in UT, making a total of 10 living

children. Times were very tough for the family in these early years. Hakan always remembered

how scarce food was. They at times had only bran and greasewood greens to eat. Hakan also

remembered sleeping on the floor between sheep skins. Many times the Anderson children

went barefoot. At times even obtaining food was difficult and settlers had to guard their wheat

at night from Indians. Wheat was $5/bushel (around $95/bushel in 2023)—if it could be found.

Hakan Julius and his siblings went to school in a large log room in Meadow. It had been planned

and built by the community for all public gatherings, including church services, dances, and the

school. It had long oblong windows and a large fireplace in the north end by which it was

heated. It was lit by tall tallow candles in holders along the wall.

The school children met all together and took turns reciting. In general, they weren’t placed in

a grade by age. Their advancement to another grade was reckoned by the number and types of

books that were completed. The school year was an average of seven months from late fall to

late spring. Later the town built a better school. The second school they attended was a twostory brick building.

6

One winter they were snow-bound. So, Håkan hired a teacher to come to the home and give the

children lessons. In the evenings, Håkan would read aloud to the family, Marie would sew and

mend, and they would all discuss the events of the day. They made their own cloth from wool

and home-grown cotton they had washed, carded and spun. Håkan was neat and careful with

what they wore. He would even have his shirts starched before working in the fields.

Håkan farmed, ran the local co-op store, raised sugar cane and made hundreds of gallons of

molasses each year to sell. He also freighted farm products and supplies as well as preserves

put up by Marie. He took the items to southern Utah towns, to the Nevada mining town of

Pioche, as well as to Salt Lake City and areas in northern Utah.

Young Hakan joined his father on these trips. They certainly needed the money they got from

this freighting and, though Hakan was nervous around the rough element and rowdy men, he

always remained safe. Hakan also helped his father lay railroad tracks from Leamington to

Frisco for the Oregon Shortline Railroad the summer he was 16. One of the cooks for this

railroad crew was Sarah Elizabeth Barney.

In Hakan’s late teen years, the Anderson children went to school in Kanosh instead of Meadow,

and thus lived with their married brother, Oscar, during the week. Hakan and Sarah Barney

were sweethearts while going to school there. Hakan, his sister Wilda, and their beaus would

spend their free time either at Oscar’s house or at Sarah’s home. On the weekends they would

go to the Anderson’s Dry Creek home where there would be dancing, parched corn or stick

candy eating, and lots of fun. The went to dances together as well, where tickets could be

bought with potatoes, squash, wheat or whatever was in season.

Sarah Elizabeth Barney and Hakan were married on the 27th of November in 1881. They moved

into the Anderson’s Dry Creek home and began farming.

After a few years, Hakan’s newly formed family. . .

. . .bought Sarah’s family home in Kanosh after her parents were called by church leaders to

settle Solomonville, Arizona. While he lived in Kanosh, Hakan rented a large herd of sheep and

ran a few of his own. His sheep herding kept him away from home a great deal. Willie

Whittaker, an orphan boy, lived at their home and helped Sarah with the farm chores while

Hakan was gone. He was considered one of the family. Sarah’s grandmother Elizabeth Barney

also lived with them in Kanosh. Hakan paid her to darn their socks so she could have spending

money.

They did well enough at first to afford nice horses and a fancy “BAIN” wagon, but two years later

came an economic reversal in the sheep herding business. Winters were so cold that Sarah kept

having quinsy—a throat ailment. So, they thought it best to move somewhere warmer with

good farm land. They decided to move to Arizona to be near Sarah’s parents.

They left Utah in the fall of 1888 and the family arrived in Solomonville on the last day of the

year and lived on the Barney Ranch. Around a year later, they moved into their own one-room,

7

12’ x 14’ adobe house located in what was called by locals either “Mathewsville,” “Fairview,”

“Hogtown”, or “Glenbar.” It was a homestead of 80 acres located on the northwest edge of

Pima, Arizona. It had its own well with water which made it very valuable land.

In Arizona . . .

. . . Hakan started freighting much like his father did in Utah. Hakan would freight coke (a type

of fuel) and goods to the mining town of Willcox, Arizona. He then hauled the copper bullion

they mined back to the railroad in Globe. He made good money doing this and bought more

property to add to his farm. He was able to build a large brick “ranch house” across the road

from their adobe house.

When the railroad was completed to Miami and there was no need for freighting anymore,

Hakan turned his focus to farming. He was on many canal boards and was integral to water

planning in Graham County. When the Smithville Canal was completed, Hakan bought extra

property from the canal company. He ended up with 600 acres of land in the Gila Valley.

1896 was a busy year in Pima. In addition to the railroad being completed, the first telegraph

reached Pima and spring water was found by Mt. Graham. This became the source of water for

all of Pima. Hakan went to the Manti, Utah temple to join family members in completing

temple work for their relatives that year. He also received his patriarchal blessing at that time.

At the turn of the century, Hakan was investing in and working at large dairies around Globe,

Arizona with his sons-in-laws. He would take his daughters along when he delivered supplies

and baled hay for the dairies. Hakan dealt with Indians many times—from his peaceful

interactions with Chief Kanosh while growing up, to being chased by Indians while on one of

these trips. The trip to Globe would take several days, and his children remembered the

interactions with Indians along the way such as attending Indian dances. They also remembered

the severe weather, fording deep streams, and various other adventures.

He was gone from home a lot during this time. All of his business endeavors did very well so

Hakan’s family soon became very well off. When he sold his shares in the dairies, he brought

the cows he had loaned the dairies back to Pima. He then needed to produce enough hay to

feed all of the horses and cows he owned. He had many hired hands who became an extension

of the Anderson family and best friends with his youngest son Guy. Some even lived on their

property. In addition to these hands, large threshing crews came yearly to put up the hay.

Hakan was a “salesman’s bonanza”–he would impulsively spend money on things salesmen

tried to get him to buy—unless Sarah was nearby to stop him. He was a very shrewd

businessman otherwise and supported his family very well. Later in his life he owned the Pima

Drugstore, part of the Lines Mercantile, and part of a movie house. He was also a director of a

bank. In the last year of his life he even raised turkeys to sell at Christmas. He was always

creating and investing in some new business idea.

8

Hakan’s family grew. .

. . .to include five girls and two boys. His girls learned sewing and all of the household chores,

but also worked on the farm outside as his sons weren’t old enough to help. Education was

important to Hakan and Sarah. He or Sarah would drive their girls by team of horses to the high

school in Thatcher on Monday and pick them up on Friday because there was no high school in

Pima.

He was a fun dad. He loved to sit in the shade and eat watermelon with his children. He had

long ropes hung from the barn’s rafters so the children could swing from one pile of hay to

another. He was a great story teller and would bounce a child or grandchild on his knees as he

recounted his childhood in UT. He could take the most trivial happening and turn it into a funny

and entertaining story. He never grew tired of re-telling the countless little tales he kept in his

head about the different members of his family.

He supplied candy, parched corn, molasses candy, and nuts when he hosted parties for his teen

children. The youth would dance, sing and be so noisy that they’d wake up their parents—who

would then join in on the fun. They were a close knit family even after the children married, as

all but one daughter put down roots and raised their families in Pima as well.

Hakan had things he liked. . .

. . .and things he didn’t. He always wore his Stetson hat—even for a haircut. He preferred to

be called HJ after moving to Arizona. He loved to sing any song, but especially the old songs.

He wanted and bought an organ for his daughter to learn and play. As a married couple, he and

Sarah went to dances in Solomonville and at Nuttall’s Sawmill.

Hakan required two ironed shirts for every day. Hakan took after his father in his concern for

neat and ironed clothes. He didn’t have to follow the fashions of the day though; he just wore

what was available and practical. Sarah had hired help around the house and one helper

commented that “I ironed and ironed. I’ve never ironed so many shirts for one family!”

Hakan loved a good joke. At least two grandchildren remembered him identifying one of the

clothes hanger hooks on the wall and announcing that this was where they would be hung for

the night. They really believed him, for he seemed so serious. He would always sit on the front

row of any performance, and his loud laughter was contagious to everyone else watching.

At first Hakan didn’t like cars. He once told his daughters before a trip: “There is only one thing

I want to warn you against and that is those new fangled contraptions called automobiles. I

hope you’ll stay out of them. I think they are dangerous.” However he soon came to love cars,

had the newest ones, and drove fast. Hakan travelled by horse and buggy long after he bought

an automobile though. Because of his size, his wagon benched sagged 8” lower on the side he

sat, which kept his wife or grandchildren climbing uphill the whole ride.

9

Hakan didn’t like meetings. Sarah was the one who saw to it that all the children attended their

church meetings on Sunday. Hakan encouraged them to go and even drove them to church in a

white topped hack. He helped pay for the new Pima Ward building. One grandson said, “I don’t

ever remember seeing Grandfather Anderson in any leadership position in the church, but I

know he was always supportive.” He was rebaptized in 1895, with his wife and three children,

when their membership records from Kanosh burned in a fire. In March as well as April of 1913

he was “appointed a home missionary” for the St. Joseph Stake.

Hakan had very jovial personality. His smile was the most becoming thing he ever wore and he

never lost it as long as he lived, even when life was hard. And hard times did happen when his

son Walter died of the flu while on his mission. “Walter died at 3:30am this morning.” was the

telegram Hakan read, whereupon he repeated “It can not be!” over and over again. Soon after

he rented out his farm to his sons-in-law and moved into town. Nine years later Sarah died. His

daughter Nora lived with him after Sarah died until daughter Laura’s family could move back to

Pima to live with him and take care of him.

Being able to drive a good car helped to ease the pain after Sarah died. He never went any

place alone in his car: he loved to visit on the drive, he wanted someone to open gates, and he

liked someone to drive horses and cows out of the way.

Every morning he went to town to get ice cream. Sometimes it would take all day. He took

grandchildren or other relatives with him. They drove through to Pima, Central, Thatcher,

Safford and Solomonville with an ice cream stop at each place.

Hakan died the 6th of June 1929 of pneumonia.